Life with Father (1939)

by Howard Lindsay and Russel Crouse

based on the stories of Clarence Day, Jr.

3,224 Performances

by Howard Lindsay and Russel Crouse

based on the stories of Clarence Day, Jr.

3,224 Performances

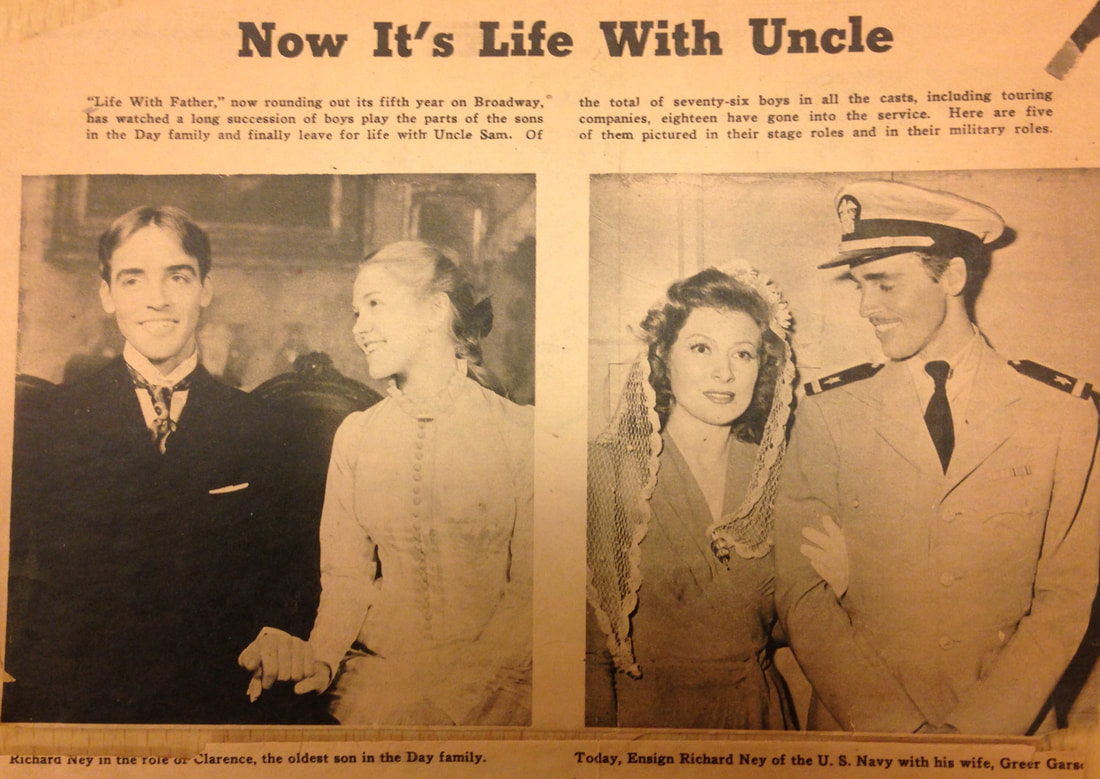

Anna Erskine in Redbook asserted that “perhaps all those concerned with Life with Father are proudest of the ex-Day boys who have been fighting for their country.” In a similar article, Helen Ormsbee of the New York Herald Tribune depicts Howard Lindsay and Dorothy Stickney, who in real life did not have any children of their own, as “vicarious parents” to the many boys who played their sons on Broadway. Stickney describes a situation that perfectly encapsulates the experience of performing in a long-running play during wartime:

Most of our boys are in training camps a long way off, but they come to see us whenever they get to New York on furlough … They say it feels like home to them to find the play still going as it always did. One of them told us, “Don’t ever stop. And when the war is over I’ll come back and play Clarence again.”

In this case, Life with Father is not just a play with nostalgic content, but is itself the source of nostalgia. The theatre has become “home,” the actress is “mother,” and the role is the civilian life that awaits at the end of the war. Ormsbee’s article can collapse these distinctions because the production has the permanence of home. The very length of the run allows Life with Father to become an object of nostalgic yearning, something to which one can “return home” because of the assurance that, whatever the vicissitudes of war, the play will endure.

Most of our boys are in training camps a long way off, but they come to see us whenever they get to New York on furlough … They say it feels like home to them to find the play still going as it always did. One of them told us, “Don’t ever stop. And when the war is over I’ll come back and play Clarence again.”

In this case, Life with Father is not just a play with nostalgic content, but is itself the source of nostalgia. The theatre has become “home,” the actress is “mother,” and the role is the civilian life that awaits at the end of the war. Ormsbee’s article can collapse these distinctions because the production has the permanence of home. The very length of the run allows Life with Father to become an object of nostalgic yearning, something to which one can “return home” because of the assurance that, whatever the vicissitudes of war, the play will endure.